14:00 Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Vortrag

Susanne Schattenberg

Der tägliche Krieg nebenan. Die Ukraine im fünften Kriegsjahr

18:00 Marktplatz Bremen

Kundgebung

Solidarität mit der kämpfenden Ukraine

19:00 Dom zu Bremen

Friedensgebet

Ökumenisches Gedenken an den russischen Überfall auf die Ukraine

17:00 EuropaPunkt Bremen

Diskussion

Zivilgesellschaftliche Unterstützung der Ukraine

Wissenswertes

Forschungsstelle Osteuropa

Die Forschungsstelle Osteuropa (FSO) ist als An-Institut eine außeruniversitäre Forschungseinrichtung an der Universität Bremen. Sie wird gemeinsam von der Kultusministerkonferenz und dem Land Bremen finanziert. Im Jahre 1982 mitten im Kalten Krieg gegründet, versteht sich die FSO heute als ein Ort, an dem der Ostblock und seine Gesellschaften mit ihrer spezifischen Kultur aufgearbeitet sowie aktuelle Entwicklungen in der post-sowjetischen Region analysiert werden.

Aktuelle PressebeiträgeWorüber Hörer der Deutschen Welle Ende der 1990er Jahre schrieben» weiterlesen Der vergeigte Putsch » weiterlesen |

Aktuelles aus Forschung & ArchivAlltagshilfe für tschechoslowakische Migrant:innen» weiterlesen Facetten nationaler Identität: Die Ukraine » weiterlesen |

Archivale des Monats

Ukrainian-German Exchange Seminar at the University of Bremen

Photo: Elias Angele.

From October 27 to November 1 2025, a group of six students from the Faculty of Philology (Ukrainian Language and Literature) at Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, together with two teachers, Oksana Matiychuk and Taras Hrynivsky, visited the University of Bremen.

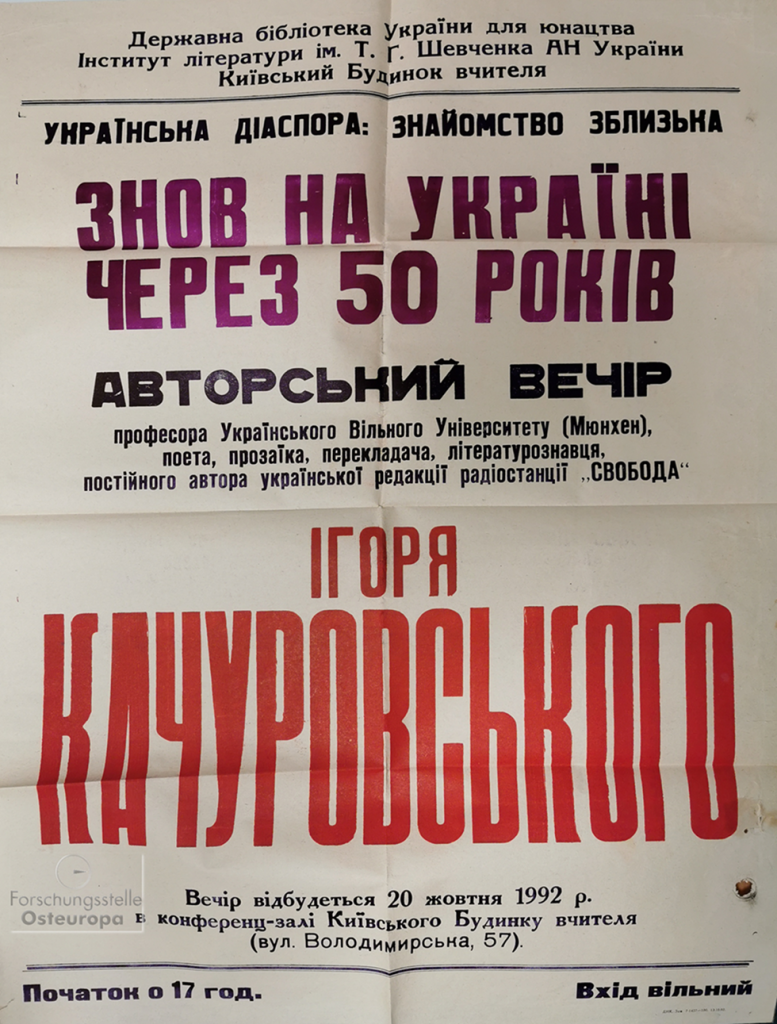

The main purpose of the visit was to work with the archival documents of the Ukrainian poet, translator, journalist, and literary scholar Ihor Kachurovsky (1918-2013), which are kept at the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen. During the stay, the students had the opportunity to become familiar with unique materials related to his life and work.

His work at Radio Liberty also took place against the background of Cold War, conflicts among Soviet émigrés and also within the Ukrainian diaspora itself. In the early 1980s, a growing influence of Russian nationalism began to assert itself within Radio Liberty. Kachurovsky became involved in recurring conflicts with the head of the Ukrainian broadcast, who was accused of pro-Soviet attitudes and exerted strong interference in editorial work as well as general working conditions, against which Kachurovsky repeatedly took a clear stance.

Later, he became a professor at the Ukrainian Free University in Munich, an institution that underscores the city’s role as an important center of the Ukrainian diaspora. Kachurovsky lived there for the rest of his life and was only able to return when the Soviet Union had ceased to exist, 50 years after he had left his home country. He was buried in his native Ukrainian village near Chernihiv.

The students worked in the archive together in mixed groups. Each participant chose a topic of particular interest, such as a specific period of Kachurovsky’s life, his poetry, his translations, his work at the radio, or his correspondences. During the research, the students studied manuscripts, letters, critical articles, radio scripts, and other archival materials. This helped them better understand how Kachurovsky’s worldview and literary legacy were formed. After working with the materials, the research results were shared and discussed. This cooperation contributed not only to a deeper engagement with Kachurovsky’s work, but also to intercultural exchange and a comparison of different approaches to literary research and archival work.

Poster advertising an event with Ihor Kachurovsky, Kyiv, 1992. Archive of the Research Centre for East European Studies. Photo: Elias Angele.

In addition to the academic program, the visit included a varied cultural program: a tour of Bremen, a trip to the German Emigration Center in Bremerhaven, a visit to the Christmas market, and several group dinners. A special highlight for the Ukrainian group was the opening of the globale° – festival for cross-border literature in the impressive Bremen City Hall. As part of the festival, Oksana Matiychuk gave a lecture on Ukrainian literature during wartime on October 29. She also spoke about the Chernivtsi-based author Inga Keivan, who joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine this year and recently announced a fundraiser for a vehicle for her unit. The audience actively supported this initiative with donations.

The seminar was made possible thanks to the support of German partners and financial assistance from the University of Bremen. The German group worked under the guidance of Elias Angele, who initiated this year’s topic and organized the seminar on the German side. Special thanks go to Professor Susanne Schattenberg, Director of the Research Centre for East European Studies, who made it possible to hold the seminar for the third year in a row.

Ulyana Melnyk, Lucia Niem, Maxim von Lücken

Ulyana Melnyk studies Ukrainian Philology at Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University.

Lucia Niem and Maxim von Lücken study Integrated European Studies at the University of Bremen.

They all participated in the Ukrainian-German exchange program.

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989