Eröffnung globale°-Festival / Kolloquiumsvortrag

19:00, Rathaus Bremen

David Safier (Bremen)

„Die Liebe sucht ein Zimmer“

Anmeldung bis 20.10

globale°-Festival / Kolloquiumsvortrag

18 Uhr (s.t.), Europapunkt, Am Markt 20

Oxana Matiychuk (Tscherniwzi)

Literatur im/vom Krieg. Ein Bericht aus Tscherniwzi

Conference: Coming to the Surface or Going Underground? Art Practices, Actors, and Lifestyles in the Soviet Union of the 1950s-1970s

Research Centre for East European Studies (FSO)

Registration until 07.11.2025

Wissenswertes

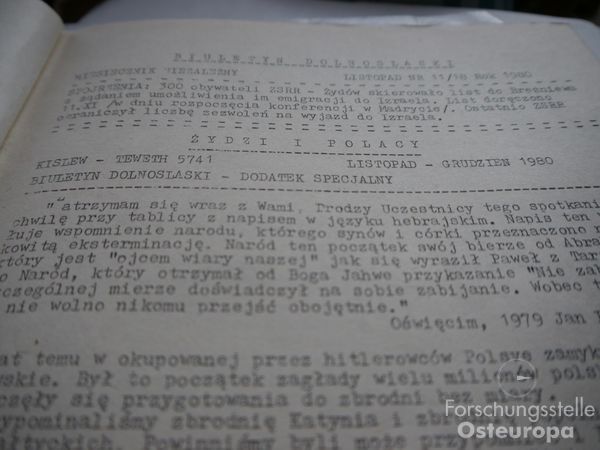

Remembering the Holocaust in the Polish Underground Press

On the 70th Anniversary of the Liberation of Auschwitz

Front page of “Poles and Jews”, special edition of Biuletyn Dolnośląski, 1980.

Source: Archive of the Research Center for East European Studies in Bremen, FSO 2-002-Gp 0034

Although the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by the Red Army was an important date in the official calendar of Communist Poland, the Jewish suffering was rarely in focus of the commemoration events in Oświęcim, which in the Polish consciousness long featured as a space of Nazi atrocities against the Polish nation. In fact, as late as in 1995, only 8% of Poles associated Auschwitz with a place of Jewish annihilation (CBOS poll). Framing Oświęcim as a universal space of suffering, where citizens of different nations were murdered, resulted both in a marginalization of the Jewish narrative in the Auschwitz Museum and, more broadly, in a reluctance of post-war Polish historians to address the difficult chapters of Polish-Jewish relations, such as anti-Semitism and anti-Jewish violence. It was only Jan Błoński’s 1987 article “Poor Poles Look at the Ghetto”, speaking of the need to debunk the myth of Polish innocence, that, in the eyes of many historians, constituted a turning point for the Polish memory of the Holocaust.

The themed edition of the unofficial Biuletyn Dolnośląski [Lower Silesia Monthly Bulletin], “Jews and Poles” issued with a double date (Kislev-Tevet 5741 / November-December 1980) gives an interesting insight into how the memory of the Holocaust featured in discussions of some intellectuals centred around Solidarity, way before Błoński’s watershed publication. Wrocław-based Biuletyn (1979-1990), which was one of the most regularly appearing underground periodicals with a nation-wide circulation reaching ten thousand copies, had a particular focus on historical issues and an ambition to address subjects neglected in the official historiography. The editorial of “Jews and Poles” states it clearly, bemoaning a widespread lack of knowledge about Jewish history among Poles: “There is problem of our ignorance. What do we know about the rich cultural, religious and social life of Jews on the old territories of the Polish Commonwealth? What do we know about their contemporary history? What can we say about their annihilation?”.

Trying to address these blank spots, Biuletyn features, among others, an interview with former Auschwitz inmate and the later Foreign Minister, Władysław Bartoszewski, an anonymous eyewitness account of the Kielce pogrom in 1946, as well as a bold essay deconstructing the myth of “Judeo-Communism” by Polish-Jewish philosopher Stanisław Krajewski (writing here under the pseudonym of Abel Kainer). The authors of Biuletyn also have the courage to call pre-war anti-Semitic violence and the so-called “bench-ghettos” at Polish universities a blemish on the Polish collective conscience and openly denounce persisting post-war anti-Semitism.

“In the aftermath of the terrible Nazi reign, the entire territory of Poland is dotted with graves, mostly Polish, but also Jewish”, writes an anonymous author under the initials of W.D. “But how differently they are treated. Walking by a grave of Polish partisans or executed civilians, a passer-by will stop, take his hat off and honour the dead with a prayer or a moment of silence. But if it’s a Jewish grave, he will say ‘damned Jew’ … spit on the grave and walk away, satisfied with himself”. And although we see some Biuletyn authors still clearly susceptible to the myth of the supreme Polish suffering – the issue reveals the very sinews of these early attempts at confronting the most painful issues of Polish-Jewish relations. Especially the freshest wounds, such as the anti-Semitic campaign of 1968, reverberate here with a poignant force. The year 1968 “has caused irreparable damage in our cultural and scientific life and has left us with misunderstandings, shame and a lot of human suffering”, writes Stanisław Krajewski. Condemning prejudice and stereotypes and pointing to the forgotten, suppressed and belied aspects of Polish-Jewish history, the special issue of Biuletyn prefigures much of the historical debates that were to unfold in Poland only decades later. Indeed, it blazes a new trail in the national reckoning with the past that even today, seventy years after the liberation of Auschwitz, is still an ongoing process.

Magdalena Waligórska

Further Reading:

Jan Błoński, “Biedni Polacy patrzą na getto.” Tygodnik Powszechny, no. 2, 1987, 1. In English: “Poor Poles Look at the Ghetto.” In My Brother’s Keeper? Recent Polish Debates on the Holocaust, ed. Antony Polonsky, 34–52. London: Routledge, 1990.

Marek Kucia, Auschwitz jako fakt społeczny [Auschwitz as a Social Fact], Kraków: Universitas, 2005.

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989