Odesa-Tage 2025

Kolloquiumsvortrag

18:15 Uhr, / Zoom

Gun-Britt Kohler (Oldenburg) | Feld, Markt, Ideologie. Der belarussische Literaturbetrieb im ersten Drittel des 20. Jahrhunderts

Conference: Coming to the Surface or Going Underground? Art Practices, Actors, and Lifestyles in the Soviet Union of the 1950s-1970s

Research Centre for East European Studies (FSO)

Registration until 07.11.2025

Wissenswertes

Joseph Brodsky’s “The Procession”

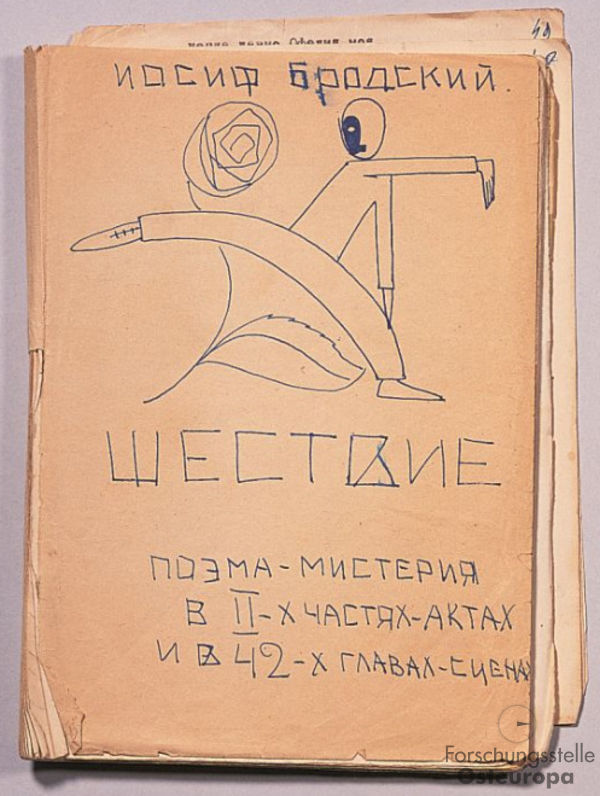

Our document of the month – a notebook of Joseph Brodsky’s long poem “Shestvie” [The Procession] – commemorates twenty years since the poet’s death in New York on January 28, 1996.

Quelle: Archiv der Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen, FSO 01-092 Sergienko

The notebook is held at Forschungsstelle Osteuropa as part of Minna Sergienko’s archive. It is a bound typescript of more than 50 pages, with corrections and marginalia, chapter titles and recitation notes inserted by the author in longhand. The cover features Brodsky’s original drawing in blue ink.

Brodsky worked on “Shestvie” for three months from September until November, 1961, and shortly after the poem was finished, he read it to a narrow circle of friends at the apartment of Boris Ponizovsky, a Leningrad artist and stage director. The envelope in which the notebook came to the archive mentions that the reading took place in the second half of November and that the notebook was “returned” to Minna Sergienko after the reading.

“Shestvie” is subtitled “a poem-mysteria in two parts/acts and 42 chapters/scenes.” In the early 1960s, Brodsky experimented with the genre of a long poem, and “Shestvie” may be read as a “sequel” to his “Peterburgskii roman” [A Petersburg Novel] written several months earlier and dedicated to Anatolii Naiman. Here, however, Brodsky defamiliarizes the setting of his native Petersburg-Leningrad and inscribes it into the world literary tradition by turning his text into a carnivalesque procession of conventional characters: Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin (from The Idiot), Blok’s Harlequin and Colombina (from his play “Balaganchik”), Grin’s (or perhaps Tsvetaeva’s) Ratcatcher, Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, etc. The roots of Brodsky’s poem have also been traced to Anna Akhmatova’s “Poem Without a Hero,” whose “vanished protagonist” – the city of St. Petersburg – is nevertheless encrypted in the original Russian title: “Poema bez geroia” (PBG). But the idea of “Shestvie,” as the author states in his preamble, is to personify our conceptions of the world, and “in this sense it is a hymn to the banal.”

The conventionality of the characters and the carnivalesque nature of “Shestvie” as a whole is counterbalanced by the comments of the narrator, who is depicted as both a participant and a witness to this literary procession. By observing it “from afar,” the young poet thus searched for his own place in this pantheon of Russian and foreign classics marching through the streets of his native city and historical era. In some sense, it anticipated Brodsky’s own imminent movement through space and time without ever returning to his native Leningrad or to the early poetic experimentation that “Shestvie” so vividly exemplifies. By 1996, his poetry had become highly laconic, condensed and even hermetic, and in this 35-year-long journey “Shestvie” serves as one of the points of departure.

Further Reading

David MacFadyen. Joseph Brodsky and the Baroque. Montreal: Mc-Gill-Queen’s University Press, 1998.

Lev Loseff. Joseph Brodsky. A Literary Life. Tr. by Ann Miller. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Yasha Klots

Länder-Analysen

Die Länder-Analysen bieten regelmäßig kompetente Einschätzungen aktueller politischer, wirtschaftlicher, sozialer und kultureller Entwicklungen in Mittel- und Osteuropa sowie Zentralasien. Alle Länder-Analysen können kostenlos abonniert werden und sind online archiviert.

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989