Odesa-Tage 2025

Kolloquiumsvortrag

18:15 Uhr, / Zoom

Eka Tchkoidze (Halle) | Medieval History in Georgian Literature and Film (19 th -20th ct.). Some Aspects of Shaping Georgian National Identity

Discussion, 02.12.2025, 18:00, EuropaPunkt

"Occupation, torture, and violations of nuclear safety", with Rebecca Harms (former MEP), Roman Koval (Truth Hounds) and Yana Lysenko (FSO Bremen). Moderated by Eduard Klein (FSO Bremen).

Wissenswertes

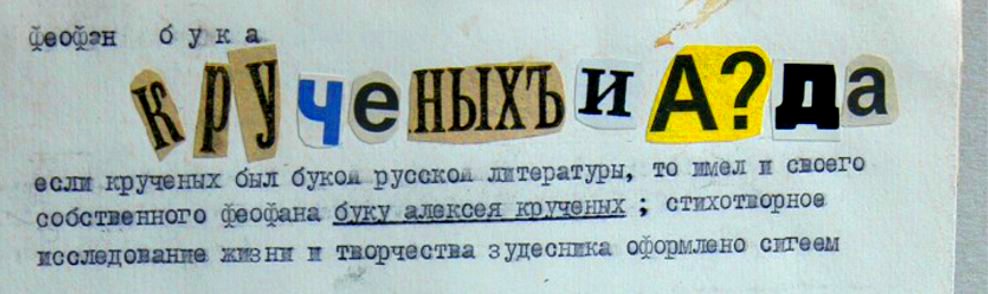

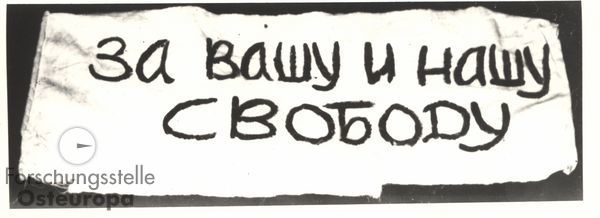

1968, Moscow Style: The Demonstration in Red Square

Fifty years ago this month, the poet Natalia Gorbanevskaia and seven other individuals protested in Red Square against the Soviet crushing of the “Prague Spring".

Quelle: Archiv der Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, FSO, 01-024 Gorbanewskaja.

The demonstration on Red Square lasted just a few minutes; most of the protesters were beaten and arrested on the spot. Gorbanevskaia, who arrived with a baby carriage containing her son Yosif along with several carefully hidden banners, was sent to a psychiatric prison. Despite the absence of any direct photographic documentation of the event itself, the August 25 demonstration in Red Square achieved world-wide fame.

я попала, но не в беду,

а в историю. Как смешно

прорубить не дверь, не окно,

только форточку, да еще

так старательно зарешёченную,

что гряда облаков

сквозь нее — как звено оков.

not into misfortune

but into history. How absurd

to carve out neither a door, nor a window,

but just a small transom,

one barred so intently,

that through it a bank of clouds

looks like links on a chain.

Further Information:

Liudmila Ulitskaia: Poetka. Kniga o pamiati: Natalia Gorbanevskaia, Moscow 2014.

Dieter Wedel: Mittags auf dem Roten Platz (Fernsehfilm in zwei Teilen), Norddeutscher Rundfunk 1978.

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989