Kolloquiumsvortrag

18:15 Uhr, / Zoom

Benjamin Goossen (Boston)

Mennonites and Lebensraum. Situating a Christian Denomination in Hitlers Empire.

Wissenswertes

Futurology and Soviet Politics

On the 50th anniversary of Andrei Amalrik’s essay “Will the Soviet Union survive until 1984?”

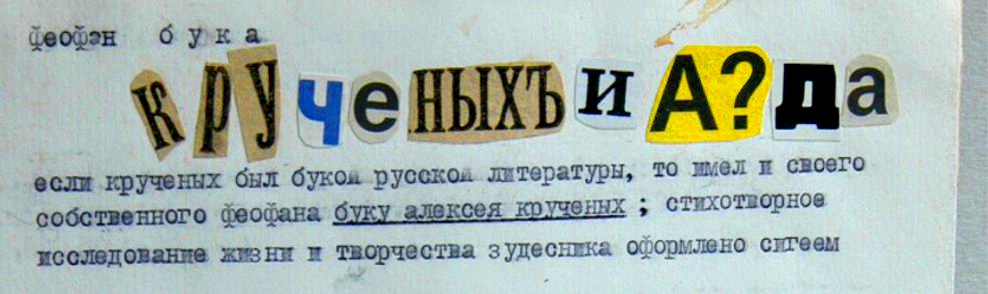

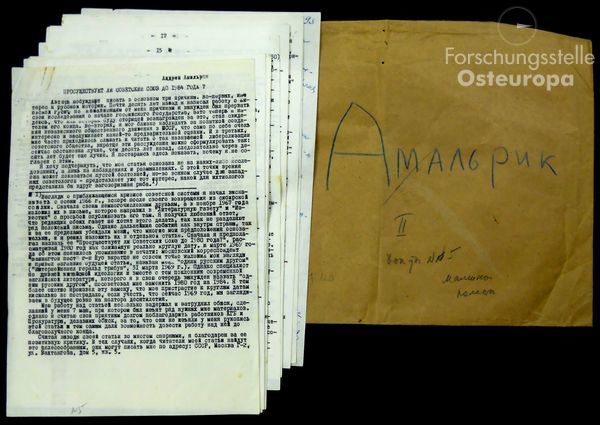

Archiv der Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, FSO 01-129. Bestand von Majja Berzina.

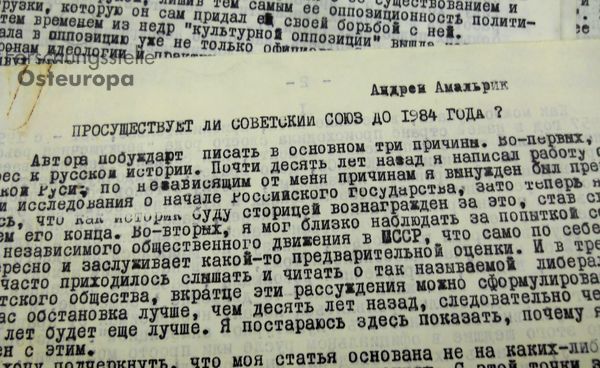

When Soviet dissident Andrei Amalrik wrote his essay in Spring 1969, few observers believed in his prediction that the USSR was doomed to collapse. Yet his analysis of late Soviet society and political dynamics was in many ways accurate and prescient. The essay became widely popular in the West and in Soviet samizdat.

Amalrik recalled that his book was a response to Andrei Sakharov’s 1968 essay On Progress, Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom. Written in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Amalrik’s work was less optimistic than Sakharov’s about the Soviet regime’s potential for reform, progressive liberalization, and détente with the Western bloc. Analyzing the development of a democratic opposition in the USSR, the dissident was pessimistic about the possibility for such a movement to expand its support base within society beyond intelligentsia circles. Instead of a process of liberalization, what he saw was a progressive decay of the system, which could no longer crush opposition, and was approaching its demise. A war with China, which would break out between 1975 and 1980, would hasten the Soviet regime’s downfall in a matter of years, just as Russia’s 1905 war with Japan had led to the 1917 revolutions. But the regime’s fall would not necessarily proceed peacefully or herald democracy: instead, Amalrik feared that growing nationalist tendencies throughout the country might lead to the anarchic and violent dismantlement of the Soviet empire.

Archiv der Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, FSO 01-129. Bestand von Majja Berzina.

Amalrik’s essay was the fruit of a discussion with a Washington Post correspondent, who then announced in the press in March 1969 that a “Russian friend” was preparing a book entitled “Will the Soviet Union survive until 1980.” The unexpected announcement compelled Amalrik to write his essay, and after changing the title to 1984, in reference to George Orwell’s work, the dissident transmitted it to the West, where it appeared on November 7. Dismissed by most observers, Amalrik’s ominous prediction was then too distant to be verified. Despite the outbreak of border fights between China and the USSR in March 1969, the hybrid nuclear-guerilla war between the two communist powers that Amalrik predicted remained fiction. Instead, the USSR engaged in a protracted war with Afghanistan, which did contribute to the decline of Soviet power. More, generally, Amalrik’s essay testified to the growing significance of the dissident movement, which was not afraid to say that “the emperor was naked.” His diagnosis of late Soviet society, pessimistic as it was, remains relevant, and explains the failure of democratic reforms in post-Soviet Russia.

First arrested for “parasitism” after his exclusion from university, Amalrik was arrested a second time in November 1970, following the publication of his essay and camp memoirs. After serving five years in a labor camp in the Russian Far East, Amalrik returned to Moscow, where he joined the Moscow Helsinki Group, a human-rights defense group founded in 1976 to monitor Soviet observance of the Helsinki Accords. Given an ultimatum to emigrate to the West, he left in July 1976. He died in a car accident in November 1980, on his way to the Helsinki Accords Follow-up conference in Madrid.

Amalrik’s essay also circulated in samizdat in the USSR. The copy conserved at the FSO archive comes from Maja Berzina’s personal papers (1910-2002). This ethno-geographer befriended many dissidents and was involved with the collection and dissemination of samizdat.

Further reading

Andrei Amalrik: Will the Soviet Union survive until 1984? New York 1971.

Andrei Amalrik: Zapiski dissidenta, Ann Arbor 1982.

Barbara Martin

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989