"Unissued Diplomas"

17:00, Europapunkt Bremen

Ausstellungseröffnung

17:00, Europapunkt Bremen

Ausstellungseröffnung

Buchvorstellung

18:00 Uhr

Annette Schuhmann

Wir sind anders! Wie die DDR Frauen bis heute prägt.

Buchvorstellung

18:00 Uhr

An Evening with Maksym Butkevych

Europapunkt

18:00 Uhr

An Evening with Maksym Butkevych

Europapunkt

Wissenswertes

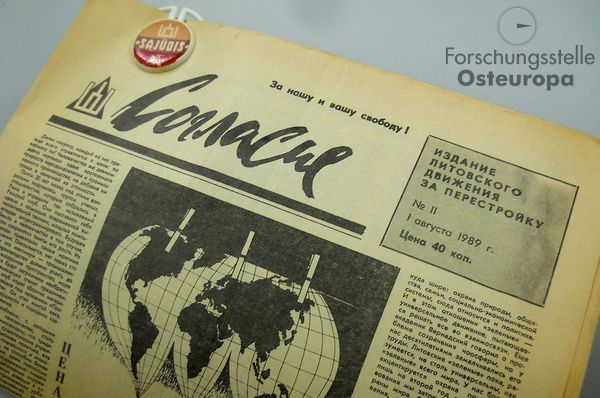

Fighting the “fake-news” in the dawn of Perestroika

On the 30th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence of Lithuania

Issue of the Lithuanian reform newspaper Soglasie from 1 August 1989. Archive of the Research Centre for Eastern European Studies. Photo: Maria Klassen.

“We have known for a long time what we are heading for, and this last step holds no more surprises. Here we are only drawing the institutional consequences of the fact that on 7 February we declared the Stalin-Hitler pact invalid,” declared the editor-in-chief of the Lithuanian reform magazine Soglasie Romanenkov with regard to Lithuania's declaration of independence from the Soviet Union on March 11, 1990. Previously, the Sąjūdis reform movement had won the first free elections for the Supreme Soviet of the Lithuanian SSR with the aim of national independence.

Since its establishment on 3rd of June 1988 Sąjūdis was the main driving force towards the path of recreation of a democratic independent state and the mass opposition movement that led the peaceful struggle for Lithuanian independence in the late 1980s. Lithuania, an independent state during the Interwar period (1918-1940), lost its freedom together with other Baltic countries as the consequence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocol. The country resisted Soviet and Nazi occupations but all the previous resistance activities and dissident attempts were smashed by the non-democratic regimes.

The Perestroika gave new hopes for democratic change. The established Sąjūdis movement also began to organise a press which was rooted in the Lithuanian dissident Samizdat publishing tradition. The first Sąjūdis publications were launched in the summer of 1988: these were semi-legal leaflets and newspapers. They were distributed by the Lithuanian cultural elite and intelligentsia, students and youth. Since 1989, better technical printing conditions were established, editing and distribution became more precise. Many of these publications, after the declaration of independence, became the first commercial newspapers of the regions, districts, cities or country-wide.

Initially, the topics of Sąjūdis publications were political – they were launching debates with the official press of the Lithuanian SSR, that was controlled and censored by the Communist party. Sąjūdis press tried to avoid what is called today “fake news”, to publish only proved facts, including the information about Sąjūdis events, criticizing local and central government, emphasizing social and ecological problems, discussing sensitive topics of history and memory, such as political crimes of non-democratic regimes. Sąjūdis press was free and uncensored, therefore soon became very popular among the readers of all ages and backgrounds. The number of publications and the circulation volumes increased rapidly.

The archival piece of the month - Soglasie - was one of these periodicals. It was published between 1989-1992 in Vilnius in Russian language (until the 13th edition of 1990 as the Supplement of the other Sąjūdis periodical called Atgimimas) and printed political, economic and cultural articles. It was distributed not only in Lithuania, but also in Russia, Belarus, Latvia, Kyrgyzstan and other former USSR republics. In 1989, the circulation was about 30,000 copies.

The fact that the journal was published in Russian language and dedicated to Russian readers in Lithuania illustrates the universality of Sąjūdis as mass movement. Lithuanian national minorities (Russians, Poles and others) were not excluded or discriminated – on the contrary, Sąjūdis was putting great efforts for every social and ethnic group of Lithuania to be represented. It was building its network according to the principles of democracy, tolerance and inclusiveness. Perhaps that is why the movement was so successful: it won the first democratic elections after the occupation of 1940 and declared the independence on March 11, 1990 – thus starting a new, democratic, Western-orientated chapter of the country.

Lesetipps

Senn, Alfred Erich: Bundanti Lietuva, Vilnius 1992 /

Senn, Alfred Erich: Lithuania Awakening, Berkeley 1990.

Monika Kareniauskaitė

Länder-Analysen

Die Länder-Analysen bieten regelmäßig kompetente Einschätzungen aktueller politischer, wirtschaftlicher, sozialer und kultureller Entwicklungen in Mittel- und Osteuropa sowie Zentralasien. Alle Länder-Analysen können kostenlos abonniert werden und sind online archiviert.

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989