Odesa-Tage 2025

Kolloquiumsvortrag

18:15 Uhr, / Zoom

Svetlana Erpyleva (Bremen) | When the War Is Next Door. How the Residents of a Russian Borderline Region Experience and Interpret the Russo -Ukrainian War

Buchvorstellung

18:00 Uhr

Annette Schuhmann

Wir sind anders! Wie die DDR Frauen bis heute prägt.

18:00 Uhr

An Evening with Maksym Butkevych

Europapunkt

Wissenswertes

Moscow Cowboy: The Many Lives of Eduard Kuznetsov

Fifty years ago, ‘Operation Wedding’ drew a spotlight on the plight of Soviet RefuseniksOn 15 June 1970 twelve passengers prepared to board Aeroflot flight Nr. 170 to Priozersk from the Smolny airfield in Leningrad. They said they were friends travelling to a wedding. Yet there was no bride or groom getting ready. There were no other guests awaiting the event. There was no wedding at all. None of the passengers intended to set foot onto Soviet ground ever again. Instead they were planning to hijack the small plane upon arrival in Priozersk, collect four further friends at the end of the runway, discard the crew and fly to Sweden. It was a daring plan. It was also a plan they knew had been compromised. Even before they entered the plane, the KGB arrested all of them. The first interrogations took place in the barracks lining the airfield.

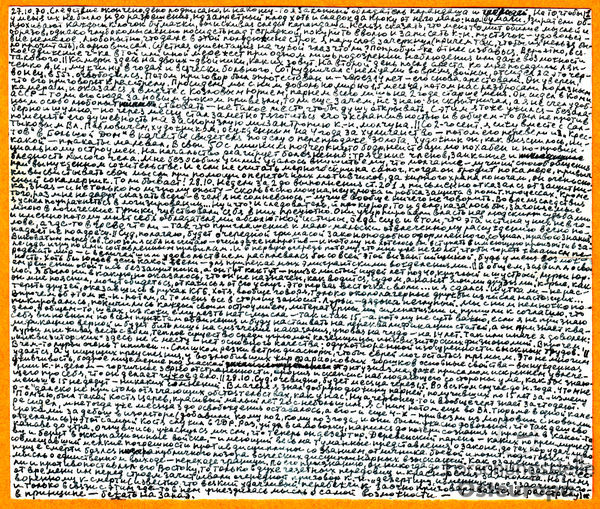

It was soon clear to investigators that the main force behind what became known as ‘Operation Wedding’ was a young man of thirty-one named Eduard Kuznetsov. It is his handwriting that is on the scrap of paper now in the Bremen archive. It was his voice that refused to go silent even when in imprisonment. The scrap of paper on display here is one of many hundreds of tightly scribbled pages, which he smuggled out of prison, and which were published as Kuznetsov’s prison diaries in Paris in 1973. It is Kuznetsov’s name that has become emblematic of the hijacking affair. The subsequent court case catapulted the plight of Soviet Jews, denied permission to emigrate, into the global spotlight, turning it into one of the galvanizing issues of the late Cold War.

In 1970 Kuznetsov was already no stranger to civil disobedience and criminal courts. Yet the KGB had previously encountered him as part of a group of young, unruly poets, reading unsanctioned texts under the Mayakovsky monument in Moscow, and as an agitator in a more select circle of youngsters planning underground activities, including – so it was alleged – the assassination of Nikita Khrushchev. These activities had sent him to prison for seven years in 1961 – a fate he shared with his co-Mayakovsky organisers Vladimir Bukovsky and Vladimir Osipov, who also embarked on lengthy dissident careers in and out of camps and mental institutions. In 1968 Kuznetsov emerged from the camps as a newly minted Jew. Upon release he opted for his father’s Jewish nationality in his passport rather than his mother’s more convenient Russian one. He also moved to Riga, where he met his future wife Sylva Zalmanson, a young woman well-connected in Zionist circles, who lead him to Hillel Butman in Leningrad. Butman, in turn, had been approached by a Jewish former military pilot, Mark Dymshits, who offered his piloting skills for a hijacking. Their plan disintegrated in stages. First, the Committee of Leningrad Zionist Organizations, which corresponded with the Israeli government, ordered the conspirators to abandon the plan, causing the withdrawal of Butman and his people. Then security was seriously compromised by co-conspirators, who spread word of the planned hijacking in a refusenik network that was riddled with KGB informers. Even the conspirators themselves knew that they would not succeed, but decided to go ahead with the action in order to draw attention to their cause.

This goal was spectacularly achieved when the Leningrad court verdict called for death sentences for Kuznetsov and Dymshits. The Western press reacted with alarm. The reaction of the wider public was indignation, if not disgust. Nixon called Jewish leaders for an emergency meeting. Under the pressure of world opinion, the Soviet Union buckled. The sentences were commuted to fifteen years in prison. It was the first of many concessions. The trickle of Jewish emigrés swelled from a few hundred to a hundred and fifty thousand in the following years. Emigration for Soviet Jews became a bargaining chip in disarmament talks and was on the agenda of almost every visiting dignitary for the next twenty years.

There was, of course, some irony in the fact that this outpouring of Jewish national sentiment was unleashed by someone who, until the mid 1960s, had not even considered himself Jewish. But Kuznetsov was a shrewd learner and adapter. Born into a rough neighbourhood, his first circle of peers were hooligans and small-time criminals until he got acquainted at MGU with the Moscow intelligentsia and their bohemian non-conformism. He soon was spearheading the battle for artistic freedom and self-expression, not without forgetting some of his earlier skills of street-fighting. During his first imprisonment he encountered the force of nationalism – not Jewish nationalism, but its Lithuanian, Estonian, Latvian and Ukrainian versions, which were ironically laced with a good dose of anti-Semitism. But, according to his own words, it was here that he discovered Zionism. The Jews had a democratic and free homeland. The Russians did not. Kuznetsov had come to conclude that the fight for reforms within the Soviet Union was futile. Hence the consequence was obvious. Russia had to be left for Israel.

At the time Kuznetsov and his co-conspirators were celebrated as heroes in most of the Western world. Yet there was always a darker side to their cause. Plane hijackings had almost been considered a gentleman’s crime. But this changed in the 1970s. Just before the trial of ‘Operation Wedding’ began, another plane hijacking shocked the Soviet Union. The Brazinkas father and son pair captured Aeroflot flight 244 from Batumi to Sukhumi, killing the flight attendant, Nadezhda Kurchenko, in the process. In Europe, too, plane hijackings for ideological reasons soon became a familiar reality and tragedy. Hijackers became known as terrorists. ‘Operation Wedding’ lost some of its gloss. But it had unleashed the power of thousands of supporters worldwide.

In 1974 Sylva Zalmanson, who had been the only woman on trial, was released on humanitarian grounds. When the opportunity arose, the US exchanged two spies for Kuznetsov and Dymshits in 1979. Kuznetvov settled with Zalmanson in Israel, where they had a daughter (Zalmanson had been forced to abort a previous child in prison). Kusnetsov worked for many years as an editor for Radio Liberty in Munich, then as the editor of the Israeli Russian-language newspaper Vesti. He divorced and married again. In 1997 he donated some of his prison notes to the archive at the Forschungsstelle Osteuropa in Bremen. He still smokes one cigarette after another. He is still known as a provocative and sometimes controversial voice. But overall, ‘Operation Wedding’ has largely been forgotten, despite the fact that the New York Times in 2010 credited it with nothing less than bringing down the Soviet Union. In 2016 Kuznetsov and Zalmanson’s daughter Anat produced a documentary about that defining moment in her parents’ lives, which distilled the story to its essence: a tale of hope and desperation by people who paid a very large price for wanting to live differently than the Soviet Union allowed.

I interviewed Kuznetsov in 2008 in his kitchen in the hills near Jerusalem. He was a congenial interviewee: smart, funny, sometimes sarcastic, well used to questions of all kinds. What stayed with me most was his desire for independence, which seemed to pour out from every word he said, if not indeed from every fibre of his body. It was not hard to believe that here was a man who had written history – on tiny scraps of paper in neat handwriting under the watchful eye of the state he hated so passionately.

Further reading

Juliane Fürst: ‘Born under the Same Star: Refuseniks, Dissidents and Late Socialist Society’, in: Yaacov Roi, (ed.): The Jewish Movement in the Soviet Union, Washington DC 2012, 137-163.

Liudmila Polikovskaia: My predchustvie …. Predtecha: Ploshchad’ Maiakovskaia 1958–1965, Moscow 1997.

Anat Zalmanson: Operation Wedding, documentary, Israel/Latvia 2016.

Juliane Fürst

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989