Conference: Coming to the Surface or Going Underground? Art Practices, Actors, and Lifestyles in the Soviet Union of the 1950s-1970s

Research Centre for East European Studies (FSO)

Registration until 07.11.2025

Bewerbungsschluss: 30.09.2025

mit Polnischkenntnissen, zum 01.10.2025

Bewerbungsschluss: 30.09.2025

mit Polnischkenntnissen und/oder Tschechisch-/Slowakischkenntnissen, zum 01.01.2026

Wissenswertes

Burned by history, but forever drawn to its afterglow

Yuriy Trifonov’s historical writing

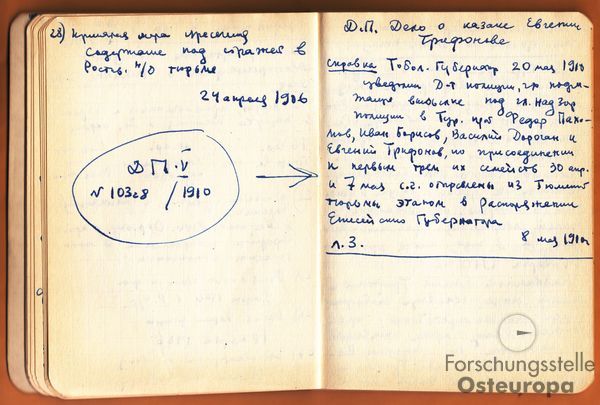

Trifonov’s handwritten excerpt of ‘Dossier on Evgeniy Trifonov’s execution’. Archive of the Research Centre for East European Studies. Photo: Maria Klassen.

For the writer Yuriy Trifonov, whose 95th birthday would have been in August this year, history was ‘a huge bonfire, and each of us throws their own wood on to it’. The offspring of an elite Moscow family of Old Bolsheviks, Trifonov was only a child when Stalin’s terror burned through his family, killing his father Valentin and hastening the death of his uncle Evgeniy. Later he would forge an astonishingly successful Soviet career out of his quest to make sense of this family trauma and to place it within 20th-century history. Nowhere did he write so directly about his own family than in Fireglow, his 1965 ‘documentary tale’ about revolution, Civil War and Stalinism. This slim book (expanded and reissued in 1966) was a major turning point, even though he never again wrote in a strictly ‘documentary’ vein. His research revealed to him for the first time the extraordinary power of historical documents: the ‘document of the month’ is taken from one of the many ‘working notebooks’ that he filled during his research for Fireglow in Moscow, Leningrad and Rostov. Although Fireglow is primarily a son’s attempt to make sense of his father’s life and death, it also compiles documents and testimonies about his uncle (whose persecution by the pre-revolutionary police is detailed here) and other family and friends who stoked the ‘bonfire’ of revolution. It largely allows these documents to speak for themselves, encouraging the reader to research and reflect on their own role in Soviet history. Fireglow also crystallised Trifonov’s shift to a more critical view of Stalinism and revolution, explored in his novels of the late 1960s and 1970s (including House on the Embankment; The Exchange; The Old Man).

Though perhaps best known as a chronicler of late Soviet urban everyday life, Trifonov was a profoundly historical writer throughout his career. The novel that first made his reputation, Students (1950) attempted to erase the stigma of being the son of an ‘enemy of the people’, a theme to which he returned in The Slaking of Thirst (1963). After Fireglow, Trifonov’s writing took an overtly historical turn. He started to experiment with historical fiction (his 1973 novel Impatience, about the People’s Will) and wrote a series of works set in the Brezhnev-era present, but with memories of earlier times subtly layered and interwoven throughout. All were the product of deep historical research: after his first foray into documentary history, his passion for archival research, family history excavation and (what we would now term) oral history interviews never left him. A key element of the Bremen archive are the dozens of notebooks where he notated this historical research throughout the 1960s and 1970s. His diaries and extensive correspondence, also held at Bremen, likewise revolve around reflections on history. It was Trifonov‘s wife Olga Romanovna who searched for a safe place for his documents and found it in Bremen. Trifonov had plans to write more historical novels before his untimely death in 1981. Still, his string of Soviet publications, supplemented by more daring works about Stalinism only published during glasnost‘, represent one of the most important bodies of Russian literature about the revolution and Stalinism. Burned by history, but forever drawn to its afterglow, Trifonov followed in the footsteps of writer-historians such as Karamzin, Pushkin and Tolstoy in researching the past, and then bringing it vividly to life.

Polly Jones

Further reading:

David Gillespie: Iurii Trifonov. Unity through Time, Cambridge 1993.

Yuriy Trifonov: Otblesk kostra, Moskva 1988.

Josephine Woll: Invented truth. Soviet Reality and the Literary Imagination of Iurii Trifonov, Durham 1991.

Polly Jones is Associate Professor of Russian and Schrecker-Barbour Fellow of University College, Oxford. She is the author of Revolution Rekindled. The Writers and Readers of Late Soviet Biography (OUP, 2019), and Myth, Memory, Trauma. Rethinking the Soviet Past in the Soviet Union, 1953-70 (Yale UP, 2013).

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989