Buchvorstellung

18:00 Uhr

Annette Schuhmann

Wir sind anders! Wie die DDR Frauen bis heute prägt.

18:00 Uhr

An Evening with Maksym Butkevych

Europapunkt

Wissenswertes

Imprisonment for political reasons

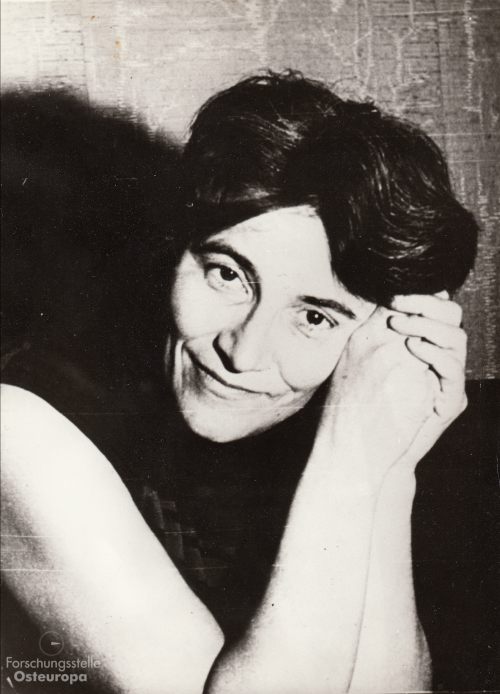

Tatyana Velikanova. Archive of the Research Centre for East European Studies, Photo: A. Smirnov.

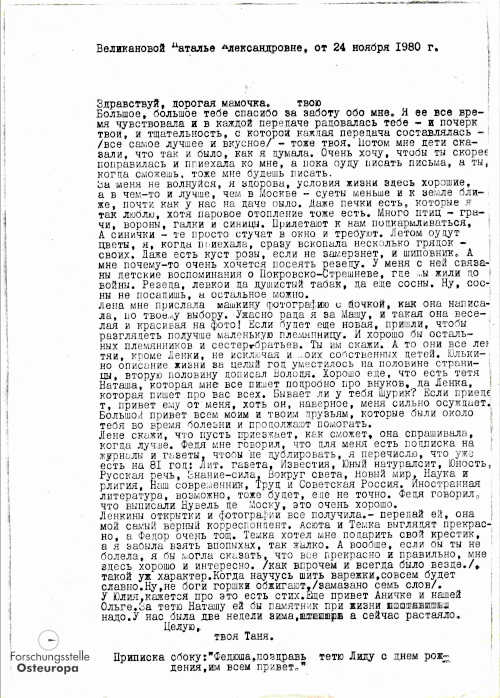

Letter from Tatyana Velikanova to her mother. Archive of the Research Centre for East European Studies, Photo: Maria Klassen.

“Hello, my dearest mother. Thank you so, so much for caring for me. I felt it all the time and with every parcel I received I was happy to feel your care — in your handwriting, in the thoroughness with which every parcel was assembled — (with all the best and tastiest things) — by you. (...) I really wish you would get better soon and come see me, but for now I will write to you, and you, whenever you can, write to me.” Tatyana Velikanova

This is the beginning of a letter written in November 1980 by the political prisoner Tatyana Velikanova to her mother. Velikanova became an active participant in the human rights movement in the late 1960s; in 1969 she was one of the 15 members of the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR. A year later, after the editor of the samizdat bulletin “A Chronicle of Current Events“ Natalya Gorbanevskaya was arrested and incarcerated in a psychiatric facility, Velikanova became one of the key figures involved in the publication of the bulletin, taking on the organizational part of the process. She stayed an editor of the “Chronicle“ up until her own arrest on November 1st 1979.

In August 1980 Velikanova was put on trial for “anti-Soviet propaganda” and sentenced to four years of prison camp, followed by five years of exile. She spent her prison term in Barashevo camp in Mordovia — the only post-Stalinist labor camp for female political prisoners.

The letter above was written a couple of months after Velikanova arrived at the Mordovian camp. Her focus is on the most innocuous topics — the weather, the smell of firewood, feeding local birds, her attempts at gardening, her grandchildren — she even compares the camp to staying in a country house; the range of topics accessible for the prisoners to mention in their letters was extremely narrow, but even in this case several words were redacted. The reality, however, differed vastly and was characterized by harsh living conditions and constant abuse by the camp administration, which prompted various forms of resistance. Irina Ratushinskaya, herself detained in Barashevo from 1983 to 1986, wrote that Velikanova established there a tradition of “zona-wide” strikes when a fellow prisoner was put in a punishment cell.

In 1984 Velikanova was sent into exile in the Kazakh SSR, where she stayed until her release in 1988, turning down Gorbachev’s offer of pardon. After her sentence was over, she returned to Moscow, where she worked as a teacher.

The letter is part of the archival collection of Natalya Gorbanevskaya, which has been in the archive of the Research Centre for East European Studies since 2002 and is regularly expanded.

With the rapid increase of political repression in recent years, and especially since the beginning of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the number of political prisoners is growing exponentially. Though Barashevo now functions mainly as a prison hospital, Mordovian penal colonies (several of which are women’s prisons) still remain a place of detention for political prisoners, among others. For example, both Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, members of the band Pussy Riot, spent the main part of their imprisonment in 2012-2013 in Mordovian labor colonies, and Ilya Shakursky, an imprisoned student and antifascist, is now in Barashevo prison hospital.

Elizaveta Olkhovaya

Further reading

Ratushinskaya, Irina: Grey is the Colour of Hope, New York 1988.

Stephan, Anke: Von der Küche auf den Roten Platz. Lebenswege sowjetischer Dissidentinnen, Basler Studien zur Kulturgeschichte Osteuropas 13, Zürich 2005.

Elizaveta Olkhovaya is a visiting scholar at the Research Centre for East European Studies Bremen and doing her PhD on female political prisoners in the late Soviet Union.

Länder-Analysen

» Länder-Analysen

» Eastern Europe - Analytical Digests

Discuss Data

Archiving, sharing and discussing research data on Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central AsiaOnline-Dossiers zu

» Erdgashandel

» Hier spricht das Archiv

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989