Lunchtalk #84

12:00 Uhr, OEG 3790

Nguyen Thi Dien (FSO)

Beschäftigung, Ernährungssicherheit und sozialer Schutz für Wanderarbeiter während der COVID-19-Pandemie

Bewerbungsschluss: 15.08.2024

40 Std./Monat zum 01.09.2024

Wissenswertes

The Samizdat Literary Collection «Sintaksis» and the Rights Movement in the USSR

Fifty Years Ago this Month, the Rights Movement in the Soviet Union was Born. Its Lifeblood was Samizdat

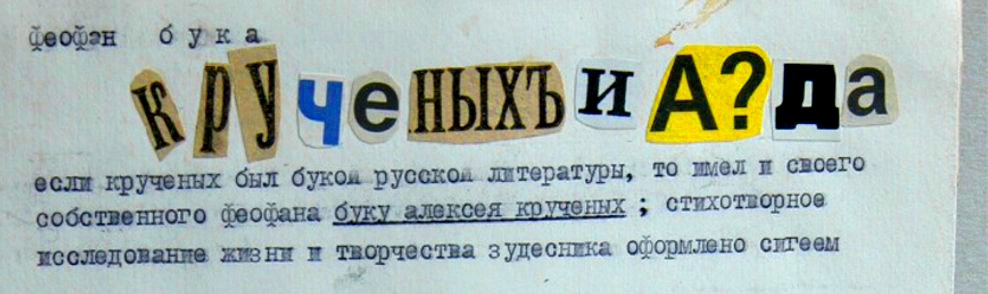

On December 5, 1965, a group of concerned Soviet citizens came out on Pushkin Square in Moscow to demand openness (glasnost‘) in the judicial proceedings against writers Andrei Siniavsky and Yuli Daniel. The date is considered the birth of a Rights Movement in the Soviet Union. According to many participants, that kind of civic activism was made possible by the independent spirit of Russian literature. Therefore, our archival document of the month is the poetry collection «Sintaksis», No. 1, 1959. This document is found in the M. S. Sergienko collection (F. 92) at the Research Center for East European Studies, Bremen. The entire issue is available electronically as part of the Project for the Study of Dissidence and Samizdat at the University of Toronto Libraries.

According to many dissidents, the values embodied in Russian literature provided grounds for independent social activism: in Andrei Amalrik’s words a “Cultural Opposition” prepared the way for a “Political Opposition.” Samizdat networks formed through the passing manuscripts of verses by modernist poets Osip Mandelshtam, Boris Pasternak and others. «Sintaksis» featured new uncensored poetry. The independent satirical works by Siniavsky and Daniel, which had been published abroad under the pseudonyms Abram Terts and Nikolai Arzhak, attracted the attention of the regime. By that time, however, it was too late. Soviet people were going to be heard.

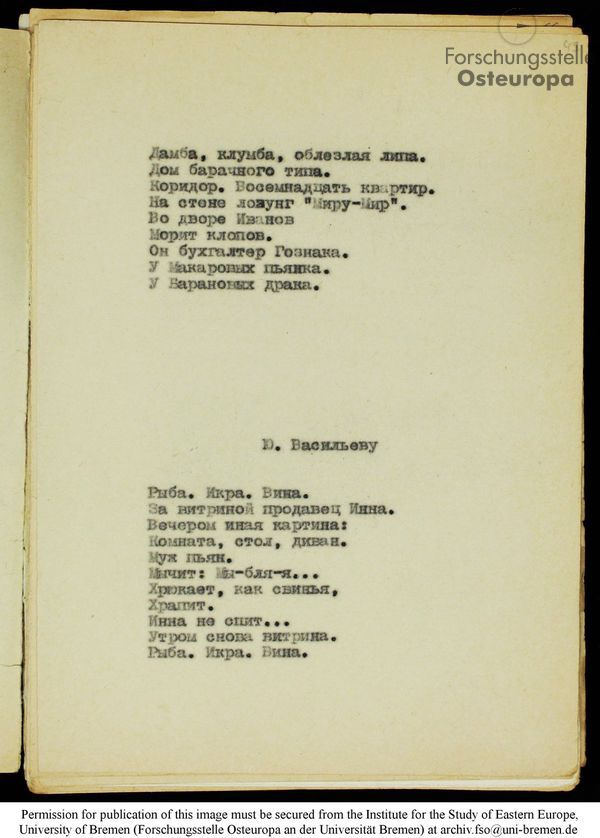

Source: Archive of the Research Center for East European Studies, Bremen, FSO 01-092 Sergienko. Contributions to «Sintaksis» No. 1 by Igor Kholin, associated with the Lianozovo school. The “barracks-style residence” (dom barachnogo tipa) in line two is a signature element of their alternative Soviet realism.

«Sintaksis» (Syntax, No. 1-3, 1959-1960), edited by Alexander Ginzburg, has been called the first samizdat periodical. The typescript issues featured verses that could not be published in the USSR by Muscovites including Bella Akhmadulina and Bulat Okudzhava (authors who did publish other works), and Nikolai Glazkov and Vsevolod Nekrasov (samizdat authors whose verses appeared in manuscript form). Issue No. 3 of «Sintaksis» featured poetry by Joseph Brodsky. The unfinished issue No. 4 reportedly would have contained works by Lithuanian poets. «Sintaksis» circulated widely among intellectuals in Moscow and Leningrad, enjoying the endorsement of well-known figures including L. E. Pinskii and G. S. Pomerants.

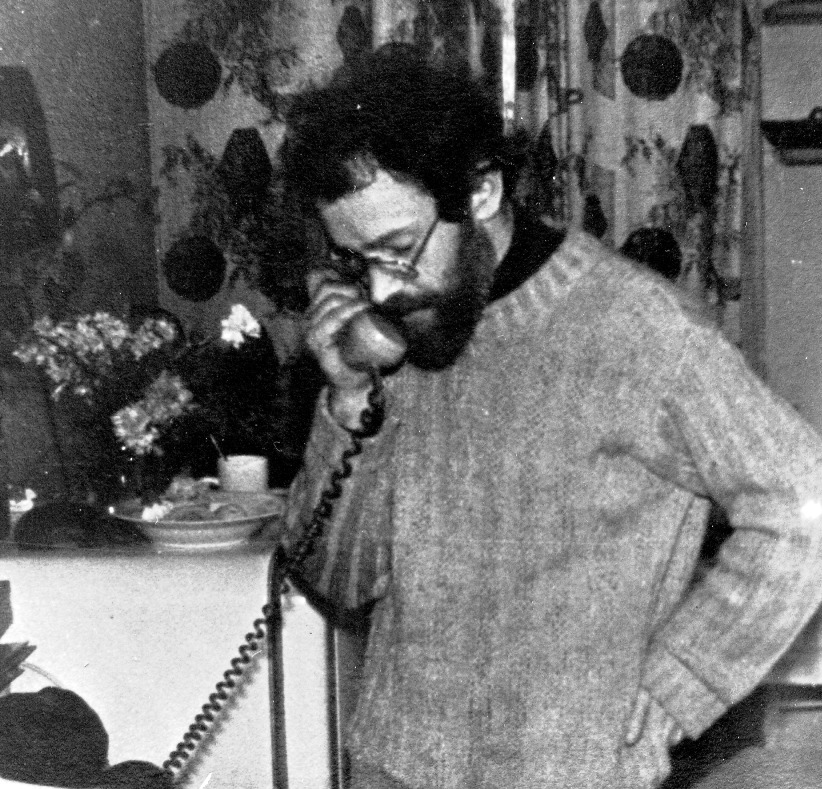

With «Sintaksis», the young Moscow journalist Ginzburg made some of the most interesting uncensored poetry available to Soviet readers, helping to unite them as an independent public through shared samizdat reading. Authorities arrested Ginzburg in 1960, interrupting the edition. Ginzburg served two years at that time. In 1966, he put together a book of materials related to the Siniavsky/Daniel case that included articles from the official Soviet press, the uncensored reactions and open letters of Soviet citizens, transcripts of the trial, and articles from the western press about the case. Ginzburg’s «Belaia kniga» (White Book) about the case circulated through samizdat networks fostered in part by his earlier collection «Sintaksis». After the «White Book» was published abroad, Ginzburg and his three collaborators – Yury Galanskov, Alexei Dobrovolsky, and Vera Lashkova – were arrested and tried in 1968 in a celebrated case that became known as “The Trial of the Four.” That trial became the subject of the first issue of the longest-running and best-known dissident publication, «Khronika tekushchich sobytii» (Chronicle of Current Events), in April of 1968.

Alexander Ginzburg, Tarusa, 1976. Photographer unknown. Archive of the Project “History of Dissidence in the USSR,” International “Memorial” Society. F. 110 (Photo collection), displayed within the Illustrated Timeline of Rights Activism

Ginzburg’s literary collection «Sintaksis» was not the first such edition. A number of independent literary editions preceded it. However, «Sintaksis» raised the level of samizdat, presenting some of the most interesting new uncensored poetry to a broad audience. Ginzburg put his name and address on the front of the edition helping set a precedent for Rights activists to assert the legality of their actions.

Further Reading:

Alexeyeva, Ludmilla. Soviet Dissent. Contemporary Movements for National, Religious, and Human Rights, Trans. Carol Pearce and John Glad. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1985. (Alekseeva, Liudmila. Istoriia inakomysliia v SSSR: Noveishii period. N’iu-Iork: Khronika, 1984.)

Komaromi, Ann. Uncensored. Samizdat Novels and the Quest for Autonomy in Soviet Dissidence. Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press, 2015, 133.

Vaissié, Cécile. Pour votre liberté et pour la nôtre. Le combat des dissidents de Russie. Paris: Robert Laffont, 1999 (Sesil’ Vess’e. Za vashu i nashu svobodu! Dissidentskoe dvizhenie v Rossii. M.: NLO, 2015).

Ann Komaromi

Länder-Analysen

Die Länder-Analysen bieten regelmäßig kompetente Einschätzungen aktueller politischer, wirtschaftlicher, sozialer und kultureller Entwicklungen in Mittelosteuropa und der post-sowjetischen Region. Alle Länder-Analysen können kostenlos abonniert werden und sind online archiviert.

» Länder-Analysen

» Caucasus Analytical Digest

» Russian Analytical Digest

» Ukrainian Analytical Digest

» Länder-Analysen

» Caucasus Analytical Digest

» Russian Analytical Digest

» Ukrainian Analytical Digest

Online-Dossiers zu

» Russian street art against war

» Dissens in der UdSSR

» Duma-Debatten

» 20 Jahre Putin

» Protest in Russland

» Annexion der Krim

» sowjetischem Truppenabzug aus der DDR

» Mauerfall 1989